Bunny Ears

It’s hard to believe it’s already the middle of February. It’s a bit sobering, really, given my lofty aspirations at the beginning of 2024. As I have mentioned before, some parts of my year of living marginally have gone better than others, and the part that is firmly in last position in terms of my achievements is decluttering. This is not because of lack of will. The fact that I am struggling to declutter is actually society’s fault.

Let me explain. I grew up Great Britain, which is a nation of hoarders – not the sad and possibly smelly Hoarders (with a capital H) of the TV show, but people who are reluctant to get rid of things…just in case. The Queen, we were told, saved string and wrapping paper. Now this was either true, and therefore a bit odd as she must have received a great number of presents over the years, or it was a PR stunt to make her seem like one of us. One thing is certain, though. Her Majesty’s generation knew much better than to waste things.

Elizabeth II was born five years after my father, so they both lived through the Great Depression, during which time, unless you happened to be an aristocrat, a farmer, or a member of the clergy, things were pretty grim. The country didn’t recover from that until World War II came rolling along, and this was mainly because the people who had formerly been unemployed were now getting killed on the battlefield and the manufacture of tanks, guns, and the like really boosted the nation’s industrial output.

My father spent the war years in the Mediterranean, where by his accounts he had the time of his life. My mother, however, was only nine when WWII began and fifteen when it ended. She was shipped off to her grandparents in Scotland for the worst of it. Having to choose between butter or jam on her bread seems to be the thing that bothered her most about wartime rationing. During rationing, Brits needed coupons for most things, and the coupons didn’t get them very much. And rationing didn’t end until 1954, nine years after the war. So, what with the Great Depression, WWII, and post-war austerity, my parents’ generation thought carefully before heading to the bin. They didn’t just throw food away, they made it into the next day’s dinner. And they didn’t just throw away things, because you never knew when you or someone else was going to be able to put them to good use.

The first place I remember living, a beautiful flat in a South Kensington square, had a junk room. That’s right – an entire room in a prime piece of real estate was dedicated to housing things my parents, well my father mostly, thought someone might need, one day. (Side note, while I lived in this square, Tara Browne crashed his car there and the Beatles wrote “A Day in the Life” about it.)

Many years later, I moved into my own first flat – okay, bedsit. I didn’t have to buy anything for the kitchenette because my father presented me with a box full of treasures from my great aunt Mary’s kitchen—which I carelessly left behind when I moved on a few months later. No matter, though, there was plenty more where that came from. I still use chopping boards, platters, serving spoons, and a beautiful paring knife that my grandmother used one hundred years ago. I am very thankful these items came into my possession after my careless phase had ended.

All this hanging on to things was essential during the economic woes of the first half of the 20th Century. And before then, people either hung on to things because they were rich and the things were valuable, or because they weren’t and once they had saved up enough for a table, that was their table…for ever. It wasn’t until Maggie Thatcher’s reign that Brits started consuming like their cousins across the Atlantic. Unfortunately, while I was brought up to conserve, I also became a fully-fledged consumer during a period when overconsumption was encouraged and greed was good. A period Harry Enfield nailed with his character Loadsamoney, who bought a new car rather than turn around the one he had parked.

If my possessions were limited to what had been passed down, in other words the way hoarding used to work, I might not now be overwhelmed by stuff and worried by the prospect of my children having to deal with it one day. And had I been born during or post Thatcherism, I probably would never have thought twice about getting rid of whatever failed to “spark joy,” in the words of Marie Kondo, who has made a fortune from throwing things away. Indeed, late 20th Century and now 21st Century capitalism depends on our being careless with stuff. Buy, use lightly, dispose of. In the last forty years I’ve certainly done my part, well the first part, but my being the product of two eras has messed up the equation, leaving me in a house that is proving difficult to Death Clean.

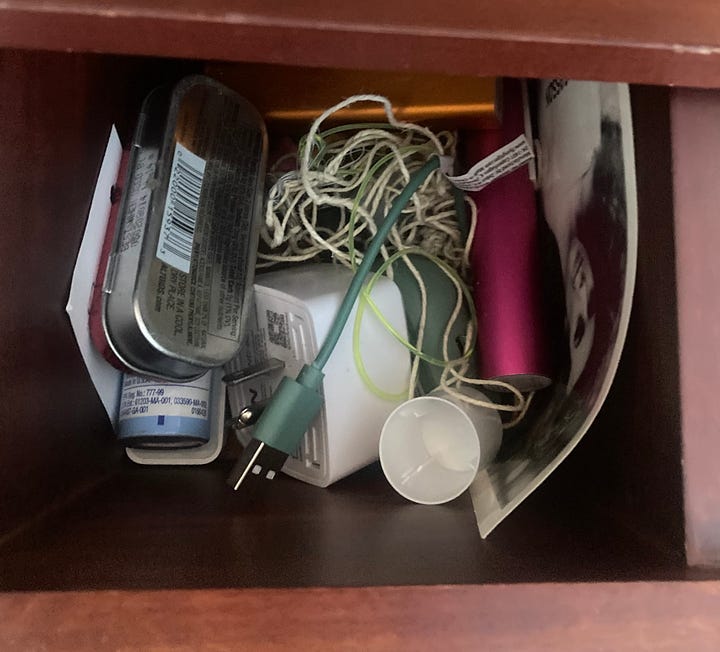

At the start of the year, I read an interesting article in which fellow hoarder (small h) Tim Jonze successfully challenged himself to throw away 50 items. Today, remembering the article and determined to do something in service of decluttering, I decided to tackle one tiny chest of drawers. As far as I remembered, it was just filled with junk. You know, a space where you cram stuff in the last minutes before guests arrive. Perhaps I would be able to find 50 items in there alone. However, thinking back to the article, I did recognize that Tim had thrown away some things that seemed to me rather a) nice or b) useful. I knew that to succeed I was going to have to be far more brutal than is my nature. But could I?

An hour later, the answer was a resounding “No.” The drawers are now very well organized, and moving forward I will be able to find a new charging cord for non-iPhone electronics the next time I need one…or two…or three. However, I didn’t come close to the 50 items. Many of the things in the drawers were simply in the wrong place, so I moved them to another drawer in another chest, to be dealt with at another time.

While not reaching Tim Jonze heights, my hour was not, however, a total waste. In addition to the organizing, I did discover one broken charging cord and a portable charger that didn’t turn on. The drawers also contained a burnt match, a dried out elastic band, a 2 inch long piece of wool, and some thread. So that’s 6 things, which is not nothing.

As I closed the final drawer, my husband casually disposed of something in the kitchen bin.

“So you threw away one cord and a set of bunny ears,” he called out, in obvious admiration of the items I had recently deposited there.

Bunny ears? I hear you ask. I suppose I should have counted them in my grand total, but they were on a lamp on top of the drawers, not in the drawers themselves. In fact, I came close to saving them, just in case my youngest daughter ever wants to dress up as a Playboy bunny again. But I discovered that a part had been melted by heat from the lamp they had been perched on for the significant number of years since she last had that inclination.

To be honest, my husband almost certainly didn’t admire today’s efforts because, until he reads this, he will not have fully understood my struggle. How could he? As an American, he was raised to believe that best things are the latest things and pretty much everything is disposable. In fact, even I didn’t understand the complexity of my struggle until this experiment made me have a good think about my life. The good news is that, to paraphrase (it turns out) many people, understanding the problem is the first step towards solving it.